|

A new antibody promotes recovery in the spinal chord and eye of rats after injury and inflammation. A new antibody targeted against a molecule known to inhibit the growth of neurons leads to recovery in an animal model of eye damage and MS. This antibody targets repulsive guidance molecule A (RGMa), which is a protein known to prevent neural regeneration and is expressed in the lesions of patients with progressive MS. By inhibiting this molecule, or preventing its action at the molecular level, researchers believe they prevent it from stopping recovery through its strong prevention of neural growth. Treatment of injured animals with this antibody against RGMa was shown to lead to increased remyelination and protection, indicating that targeting RGMa may be a viable method for regeneration therapy in MS. Link to article

Quest for new markers of MS disease in spinal fluid. The current standard for tracking disease in the central nervous system (CNS) is through MRIs, however, the presence of lesions found in the CNS through MRIs are not always associated with inflammation and relapse. This makes it difficult to diagnose and track disease progression. Using a variety of tests to determine the kinds of immune cells and other molecules called proteins in the spinal fluid of patients with relapse remitting MS (RRMS), primary progressive MS (PPMS) and other neurological conditions, researchers have found newer biomarkers that may help to better diagnose and track disease in patients. The presence of one protein, called sCD27, was shown to be highly predictive of CNS inflammation, along with other standard methods such as detection of another protein called IgG. It was also found that the presence of IL-12p40 was shown to accurately categorize MS disease subtypes, highlighting its potential use in diagnosis. In summary, this model, or decision process based on many measured factors from the CNS, can help to characterize patients disease and aid in diagnosis, which is notoriously challenging. Future work should build upon this model, where many measured factors can help to better diagnose and track disease over time, specifically in the CNS where disease is most active. Link to article BREMSO: a new score for predicting course of MS disease. The ability to accurately predict the course of a complicated disease like MS would be beneficial to both patients and doctors by helping to inform treatment. Currently, no such summary score to help in this process exists, and disease progression prediction depends primarily on several different clinical factors that have not been combined in a useful way. Using data derived from MSBase, a data base of MS patient data, researchers have proposed such a predictive score called Bayesian Risk Estimate for MS at Onset (BRMSO). In short, a score is generated from clinical factors and demographics collected at disease onset, where patients with higher scores progress and those with lower scores are more likely to not progress. Overall, the researchers suggest that this new score be used to assess clinical trial outcomes or as a method to assess treatment outcomes, and could be used to inform treatment. Future work could benefit from including MRI information in the score, since this is not included currently, potentially due to the lack of clear MRI data in existing MS databases. Link to article A call for more and better disease modifying treatments (DMTs) for MS. Relapses are a significant aspect of multiple sclerosis, and characterization of how relapse rate correlates with DMTs and more broadly to patient experience essential to better understanding relapses and how to better help patients. In order to evaluate treatment through individual patients, the North American Research Committee on Multiple Sclerosis (NARCOMS), administered a survey to 1000 participants. It was found that the most commonly reported treatment was corticosteroids, and neither gender nor MS type were associated with received treatment or current DMT. An average of ~7 new symptoms were reported to be associated with new relapses, mostly from patients with progressive MS, and the most commonly reported symptom of relapse overall was fatigue. Beyond all of the statistics, its clear that many patients reported effects of a relapse on life activities, including working and going to school. About three months after a relapse, only about half of the patients that responded reported feeling better. The authors admit their study was limited by those patients that responded to their survey, however their conclusions are clear: there is a need for improved DMTs given that patients with MS continue to experience relapses and the negative impact these episodes have. Link to article Certain factors promote growth of choroid plexus cells. A type of cell called epithelial cells make up the choroid plexus, or tissue that produces spinal fluid in the brain. These cells are thought to be important because they make up the blood-brain barrier that protects the brain and can promote repair of injured brains. These cells grow very slowly, and it would be beneficial to identify factors that promote their growth, which could aid in recovery of brain injury. The authors of this study identified certain factors, mainly growth factors like epidermal growth factor, which promote the growth and recovery of these cells in mice. Future work should extend these to human cells, as well as explore additional growth cues that can promote repair and how growth might lead to improved function in the context of disease like MS. Link to article Multiple Perspectives in Multiple Sclerosis is written by Brittany A. Goods, a PhD candidate at the MIT Department of Biological Engineering, and edited by Deborah Backus, PT, PhD, Director of Multiple Sclerosis Research at the Shepherd Center in Atlanta, GA.  Genetic risk factor increased in women, may be linked with disease severity. A new study has found that a change in the gene STK11 may occur more often in women with MS, and may be related to less severity of the disease.

A closer look at how cells die in MS lesions suggests that a new drug might be useful for treating MS. Researchers showed that a substance that blocks certain enzymes stop the damage to the myelin in experiments using mice with MS and in culture experiments with human cells. Not only does this tell us more about disease mechanisms, but it also provides something new to target for MS therapy.

Big data in MS requires central database. One way to collect and store a lot of data from a lot of people is to build a structure to hold the data. This is called a database. Having a large database with information from a lot of people with MS, such as the imaging of their brains with MRI, will let researchers track data easily and over time. This will allow researchers to look for patterns and trends in the data. Early work in the eFolder project builds the framework for such a database that will be open to any person with MS and will allow researchers to be able to get to the data, and to look for relationships in the data.

GM-CSF: traffic control cop of blood-brain barrier. The blood-brain barrier protects the central nervous system from cells that cause the inflammation in MS. One type of cell has been shown to be related to the cause of MS in many ways. This cell is called the granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). A study in the European Journal of Immunology has shown that GM-CSF makes it easier for monocytes, a kind of immune cell, to get across the blood-brain barrier.

If you haven't already registered with us, please Register Now to receive Multiple Perspectives in Multiple Sclerosis (MPMS) weekly! CLICK HERE For more on these topics, click on the "READ MORE" below Multiple Perspectives In Multiple Sclerosis (MPMS) is written by Brittany Goods and reviewed and edited by Deborah Backus PhD Featured Project Genes and Environment in Multiple Sclerosis (GEMS)

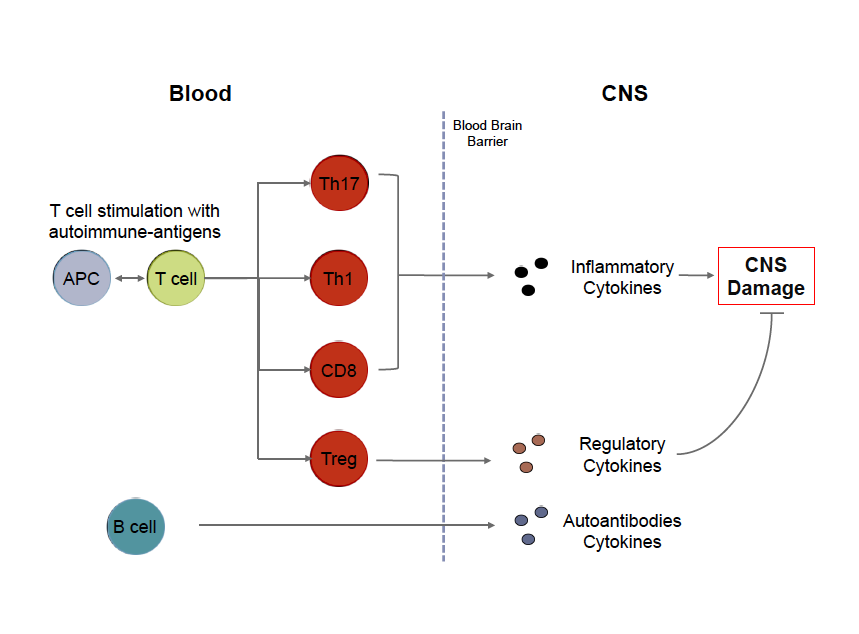

Mission The Genes and Environment in Multiple Sclerosis (GEMS) Research Study is dedicated to identifying genetic, environmental and immune factors that may increase a person’s risk of developing MS. Description This research study will ultimately enroll 5000 subjects who are at risk of developing MS. This increased risk is correlated with having a first degree relative (parent, sibling, or child) with MS or with having taken certain Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNFa) agents. Obtaining information about who is at risk for MS will be beneficial in the future in identifying effective ways to screen or prevent this disease. Who can participate? People between the ages of 18-50 that are either: - First Degree Relatives (parent, child, sibling) of a patient with MS, or - Diagnosed with MS or other demyelinating disease by a neurologist and has at least one first degree relative with MS. -Have taken or are currently taking one of the following anti-TNF therapies: ~ Adalimumab (Humira) ~ Infliximab (Remicade) ~ Etanercept (Enbrel) ~ Certolizumab (Cimzia) ~ Golimumab (Simponi) Do you have to live in Boston to participate? - No, we are recruiting first degree relatives from all parts of the United States as we do most of our recruitment through mail, phone, and email. Contact us for more information For more information, please visit our facebook page or email us at bwhmsstudy@partners.org #MultipleSclerosis, #MS, #Cells, #Immunology By Brittany Goods  My goal with writing these posts is twofold. First, I'd like to present an introduction to key scientific concepts in order to help readers better understand MS research. Second I'd like to provide a resource and scientific opinion about current MS topics, ranging from therapy to basic biological research. Throughout each post, I will also try to provide links to peer reviewed open sources for readers that are interested in learning more details! Cells of MS In order to fully understand the cause of an incredibly complex disease like multiple sclerosis, it can be argued that we need to better understand the biology and hence the dysfunction of the cells that are responsible for mediating disease. It is now widely accepted that MS is an inflammatory disorder affecting the gray and white matter of the central nervous system. Whether MS is an autoimmune disease in the traditional sense, meaning that ones own immune system targets part of the body for destruction, is still a matter of considerable debate. Regardless of how this debate is resolved the cells of your immune system are involved in the pathogenesis of MS. One of the most basic questions you can ask is what role each immune cell plays in the context of MS, and further, how can we better understand what is wrong with these cells so we can fix them in a targeted way? There is a lot of technical information available to patients with MS, but they aren't often presented in a way that can be easily interpreted. I'm writing this post to give an overview of what is important about some of these key immune cells, with a focus on T cells, and hopefully provide an introduction to these without too much jargon and acronyms that inevitably complicate immunology. For those who are interested, each term in bold is linked to an open source article with a focus on MS where possible. The immune system is comprised of a vast network of specialized cells that work in concert to protect us from infection and help heal injuries. There are two arms of this system: innate and adaptive. The innate branch of cells are the first responders that are designed to sound the alarm that something is wrong. These cells are the infantry of your immune system: they're always there, ready for anything, and will report what is going on to their 'commanders' in the adaptive branch. The adaptive immune system is designed to learn about what's wrong so when the body sees the same problem they can be poised to respond quickly. In the same vein of army analogies, these cells are like the special forces. They're trained very specifically and shape the evolution of a given immune response. In the context of MS, a kind of adaptive cell called a T cell recognizes components of the CNS and initiates an immune response. Thus, T cells become activated in response to specific proteins they recognize, called an antigen. These protein antigens may be present in many different cell types in the brain although most researchers focus on protein antigens present in the myelin produced by oligodendrocytes. There are many different flavors of T cells that can arguably be broken into three main types: helper T cells, regulatory T cells, and cytotoxic T cells. Helper T cells, also called CD4 Th cells, become activated by specific antigens, such as myelin, that they recognize through specialize surface receptors. These activated cells exert their function by producing cytokines, proliferating, and expressing molecules that allow them to travel to specific sites in the body so they can activate other immune cells. In the context of MS, two types of Th cells called Th1 and Th17 cells, are implicated in disease. I will write a later post specifically focusing on these cells and what we know about them and what this might mean from a therapeutic standpoint. Regulatory T cells, also called Tregs, are needed to limit this response or turn off this response when needed. Without these cells, the signals provided by Th cells can amplify unchecked. Finally, cytotoxic T cells, also called CD8 T cells, are most important for killing cells that are infected with the antigen they recognize. These cells are kind of like the cleanup crew of an immune response. B cells are another kind of adaptive immune cell that produce antibodies that act as molecular tags to signal that the antigen they're bound to shouldn't be there. Interestingly, a few key things make the role of B cells a little more complicated: 1) B cells actually need help from T cells to begin this process, 2) B cells can activate T cells (act as what are called antigen presenting cells), and 3) B cells can modulate T cells by also secreting cytokines. For a very comprehensive review of immune cells as they pertain to MS, please check out this review. Adapted from Weiner, 2009.

B cells and T cells are the immune cells most implicated in disease based on both genetic studies and the success of treatments like those that deplete B cells (i.e.: rituximab) and prevent immune cells from trafficking to the CNS (i.e.: nataluzimab). There are still many outstanding questions about these myelin-reactive T cells and B cells as well. For example, the immune system has many checks in place to prevent the development of autoimmunity, so how is it that these cells arise? What makes these cells fundamentally different, since it has been shown that myelin-reactive T cells can be found in people that do not have MS? For B cells, how do these cells become activated to produce antibodies in the CNS? How do these cells activate T cells, which can ultimately lead to myelin-damage? Finally, how do these cells get into the CNS? My next few posts will review the science behind stem cell transplants as a therapy for MS, as well as newer genetic studies that have revealed key insights into the cells discussed above. Stay tuned and please post any questions, and future posts can address these! Other sources: "Multiple Sclerosis Immunology: A foundation for Current and Future Treatments," Takashi Yamamura and Bruno Gran. 2013. #cellsofMS #MSimmunology Brittany Goods is a doctoral candidate in Biological Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She received a Bachelor of Engineering degree at Dartmouth College and a Bachelor of Arts degree in Biochemistry at Colby College. She is currently an NSF graduate research fellow at MIT in Chris Love’s lab. Her research is focused in clinical immunology, with the goal of applying novel computational and experimental techniques to study multiple sclerosis. Ultimately, these efforts towards better characterization of cells responsible for initiating and propagating disease will facilitate insights into MS pathogenesis and reveal novel therapeutic targets. By Deborah Backus, PT, Ph.D.

Director of Multiple Sclerosis Research, Shepherd Center Have you ever heard about a research study and thought that although the research pertains to MS, it has nothing at all to do with what you think people with MS need? Or have you heard the phrase “Experts say that people with MS…”, or something similar, and wondered who are these “experts”, and how do they know as much as I, the person with MS, knows about the experience of MS? Now, can you imagine taking your thoughts and your ideas about what you need or want to know about MS, treatments, rehabilitation options, and turning these into research questions? Can you conceive of influencing the questions that researchers ask about MS? The creators of iConquerMS™ did. Part of a national research network, called PCORnet, iConquerMS™ is a unique research initiative that is driven by and governed by people with MS. That means people with MS “call the shots”. The collaborative partnerships created by iConquerMS™ between people with MS, researchers, and healthcare providers will help define the most meaningful research questions and the best ways to answer them to improve the care of people with MS. How does it work? IConquerMS™ is accessible through the iConquerMS.org website/portal. At this portal, people with MS can securely submit their health data, for the collection of large amounts of data from multiple people with MS. This data can be used by researchers to look deeper into issues related to MS, to find patterns and connections across the group that might not be evident in a single individual, or across smaller groups. This big data research in MS may help answer questions related to what is important to people with MS, the causes of MS and the strategies that might prevent it, cure it, or stop progression of disability, and which treatments work best in different individuals. As a person living with MS, your information has power. Because your experience with MS is unique, your data is imperative for learning more about the progression of MS and the treatments that are most effective in stopping progression of disability, alleviating the symptoms of MS, and improving your quality of life. What do you get from participating in iConquerMS™? As a registered user of iConquerMS™ you not only privately enter your data, but you will be able to interact with other people living with MS and the researchers hoping to beat MS. iConquerMS™ will also provide updates on how the data is being used and keep you informed about the insights emerging from the research. You will be on the frontline of research that will more likely make a different in your life. Go to iConquerMS.org. Help iConquerMS™ researchers solve the problems most meaningful to you. Is This Article About Stem Cell Transplantation Important For People With Multiple Sclerosis?1/25/2015

A colleague recently sent me an article (Nash et al JAMA Neurol. Published online December 29, 2014) about early results from a study of the safety and effectiveness of stem cell transplantation in people with MS. She asked me what I thought and if I thought this was important for people with MS to know.

First and foremost, it is always important for people to know about research that is meaningful to them. Thus, this research related to stem cells in people with MS would be something that people with MS might want to know about. However, it is critical that people understand the research that was done and the implications – independent of the news headlines reporting it. Stem cell research is not unique to MS. Since stem cells have the potential to develop into different cell types over the course of one’s lifetime, they also offer promise for treatment of various diseases, such as heart disease, stroke, Parkinson’s disease and diabetes. There is also research directed at repair after injury, such as spinal cord injury and burns. Although there is excitement surrounding stem cells as a potential to cure disease and injury, there is also a tremendous amount of research yet to be done to determine the best way to deliver stem cells, and whether or not they are safe and effective for people with MS, or any of the other diseases or injuries for which they are being used. For this study, researchers used peripheral blood stem cells obtained from the person with MS them self (autologous). This treatment was combined with high dose prednisone before and after the stem cells were infused into the participant’s body in order to prevent relapse and fever. Chemotherapy was also provided daily before the stem cells were infused. The researchers are mainly interested in “time to treatment failure” during the first 5 years after treatment. This means that they are monitoring participants for disease activity or disability due to MS, such MS-related lesions in the brain or a relapse, or a change in function measured by a scale called the Kurtzke Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS). One question that a person with MS should ask about this study is “who were the people in this study that received the stem cell therapy?” The participants in this study are between 18 and 60 years of age, with relapse remitting MS (RRMS) for less than 15 years. They had to have an EDSS score of 3.0 to 5.5 when enrolled into the study, which means that they could still walk but may were limited in some daily activities. Participants had to have failed disease modifying therapy, meaning that they had 2 or more clinically defined relapses during 18 months of therapy and an increase in the EDSS score that remained for 4 or more weeks. So, the results of this study will most directly apply to people with these characteristics. Children and adolescents are not receiving the treatment; nor are people over 60 years of age. People with EDSS scores greater than 5.5, who present with more disability, also are not included. Thus, the findings of this study may not apply to children, adolescent or older adults, or those with greater disability. It is important to note that this is a Phase 2 clinical trial and therefore there is not a control group. Therefore, the outcomes in these participants are not compared to a group that did not receive the treatment. That makes it difficult to know if the treatment itself is what led to the changes that are reported. The researchers did try to adjust for this by taking measures at several time points, and also by comparing their data to that from other related studies. What are the outcomes thus far? Does the infusion of these stem cells cure MS? Does it at least prevent relapse? The outcomes are more promising than an earlier study comparing a disease modifying therapy (natalizumab) to treatment with no disease modifying therapy. Specifically, in this study the survival rate (the rate of no relapse for a specific time) was estimated to be 82.8% at 2 years and 78.4% at 3 years, compared to 37% and 7%, respectively for the earlier study. An important note is that in the earlier study, the participants had a wider range of EDSS scores, from 0 to 5.0. The earlier study was conducted in people with less severe disability (lower EDSS scores), but the survival rate was higher (better) in this study with people who had greater disability (higher EDSS scores). The paper also reports that unlike earlier studies of disease modifying therapies, participants in this study experienced improvements in function, and a decrease in disease activity, in the first 3 years. Function was measured with a functional outcome scale and the EDSS; disease activity was measured as the number of relapses and survival rate, and MRI (imaging of the brain). Participants also reported an improved quality of life. However, treatment was deemed to have failed in 2 participants after the first 3 years. The investigators will continue to follow the remaining participants through 5 years to confirm what they have already observed. Another question someone should ask about results from a research study is whether or not there were adverse events, or any negative outcomes, in any of the participants. It is important to remember that this stem cell treatment is associated with significant risks. There were a number of adverse events reported, but most were what one would expect. Adverse events ranged from gastrointestinal disorders, and infections, to nervous system impairments, such as headaches, changes in sensation, and blurred vision. There were also reports of deep vein thrombosis, cardiac impairments, and pulmonary problems. Out of 24 participants, there were 2 participants who experienced an MS exacerbation, one of which died 2.5 years after treatment with stem cells. The findings from this study are similar to those in another report of a case series in which people with MS were treated with immune-suppressing therapy followed by transplantation of blood stem cells (Burt et al. JAMA. 2015;313(3):275-284).In the 145 participants with RRMS followed for up to 5 years after treatment, EDSS scores improved in 50% (41 of 82) of the participants at year 2, and 64% (23 of 36) of participants at year 4. Disease activity was also reduced. The authors of that case series reported that people with secondary progressive MS and those with disease duration greater than 10 years did not demonstrate the same improvements So, what do I think? I think that there are some promising findings, but that In order for any treatment to be considered as a reasonable option by people with MS, the effectiveness will need to outweigh the risks. Much research is required before deciding if treatment with these autologous stem cells is effective for halting the progression of disease activity and disability due to MS. This will require not only completion of this 5-year study, and comparison to other trials, but well-controlled clinical trials before we will know if the effectiveness is greater than the risk for people with MS. Deborah Backus, PT, Phd Director of Multiple Sclerosis Research Shepherd Center

Q: I live on Long Island and would be interested in participating in a clinical trial for Anti-Lingo. I hear that such a study is being done this year at Stony Brook University. I currently suffer from the early phases of secondary progressive MS, having been diagnosed in 2006 with Relapsing Remitting MS. I am a 55 year-old male, ambulatory (although I do walk with the assistance of a cane. Thank you.

A: ClinicalTrials.gov and CenterWatch are good places to check regarding clinical trials. After checking these sites, we didn't see any trials for anti-lingo in the Long Island area, so we contacted Stony Brook University directly and they were not aware of any either. Finally, we contacted Biogen-Idec and they said to speak with your physician about any possible future trials. |

Archives

April 2015

About Dr. Debbie

Deborah Backus, PT, PhD is Director of Multiple Sclerosis Research at the Shepherd Center in Atlanta, Georgia. Dr. Debbie received her B.S. in Physical Therapy in 1986, and her Ph.D. in neuroscience in 2004. Categories

All

|

- Home

- About Us

- Virtual MS Center

- News & Resources

- Seminar Registration

- Health & Wellness

- Blogs

- About MS

-

Symptoms

- Balance and Walking Issues

- Breathing/Respiratory

- Bowel Dysfunction

- Cognitive Dysfunction

- Crying/Laughing Uncontrollably (PBA)

- Depression and Anxiety

- Dizziness/Vertigo

- Dysphagia

- Fatigue

- Foot Drop

- Hearing or Smell or Taste Changes

- Heat Sensitivity

- Leg Weakness

- Loss of Hand Dexterity and Coordination

- Memory and Mutliple Sclerosis

- Migraines

- Numbness/Tingling/Altered Sensation

- Nystagmus and Oscillopsia

- Pain

- Sexual Dysfunction

- Sleep Issues

- Spasticity/Spasms/Cramps

- Speech/Swallowing

- Urination/Bowel Problems

- Vision

- MS Clinics

- MS Topics

- Register With Us

- Terms of Use/Privacy/HIPAA

- MS HealthCare Journey

RSS Feed

RSS Feed